Jack’s group

followed the front lines pushing back against the Germans. Paris had been

liberated by the French Resistance in August 1944 and Allied troops soon

followed, officially and on pass. Jack photographed the famous Champs Élysées Boulevard

where German troops had proudly asserted their authority over the French

capital in 1940 and General Charles De Gaulle had strolled after liberating the

city. By the time Jack arrived, the city looked almost itself again.

|

| “General de Gaulle and his entourage proudly stroll down the Champs Élysées to Notre Dame Cathedral . . . 25 August 1944”[1] |

|

| The Champs Élysées as Jack saw it |

|

| Winkler at the Palais de Chaillot |

|

| Jack with the Eiffel Tower and the Palais de Chaillot in the distance |

|

| Indulging in one of the things they missed most from home: ice cream |

The Push through France

Now that he was

moving through Europe, Jack was able to tell Alice where he had been in England

and France over the previous ten months. It was a secret no more.

|

| Keevil > Rivenhall > Stapleton > Maupertus > Montebourg > La Bazoge > Saint-Dizier > Luxembourg[2] |

Europe,

Oct 17, 1944

Dearest

Alice,

Well

honey I suppose you have wondered many times where we have been since coming

overseas. We landed in Scotland & took a train to England & went to a

place called Keevil. It’s very small & probably not on the map but it’s

near Trowbridge which is near Bath. From here we went to Rivenhall. That’s near

Witham which is near Chelmsford. From here we went to Staplehurst which is near

Maidstone. From there over to France & I arrived just outside Cherburg on

July 4 where we were stationed for some time. From there we went to a place

near Monteb[o]urg. From there to La Boyoge [La Bazoge], just outside of Le Mans.

Then when Derrick & 4 other fellows & I were away on Detached Service

we were at Saint-Dizier. From there we left France and are at our present base.

I’m sure glad you got the bracelets

& I’m glad you like them. They aren’t much but they are a souvenir of

France. I got them at St. Pierre-Eglise [near Cherbourg].

I

don’t know what kind of fish they have in France but the ones we caught were

just big enough to throw back in.[3]

On

Detached Service at Saint-Dizier, France

|

| A sign on the door of the restaurant of the Hôtel de l’Univers takes clear aim at Allied soldiers. It reads in English, “Off Limits.” |

|

| Signs on the Saint-Dizier theater read, “Honor to our liberators” and “Long live the Republic.” |

Living Quarters as the Group Moved from Base to Base

Jack explained

to his grandchildren about the living quarters during his time in the ETO: A tent holds

six soldiers or beds. There wasn’t room enough for a bathroom in the tent. The

bathrooms didn’t have roofs on them. (Some of them did.) And they got wet.[4]

|

| Morning at the tents |

|

| Constructing a latrine: Toy, Judge, Metler and two loafers |

|

| Finished latrine with Judge and Metler |

|

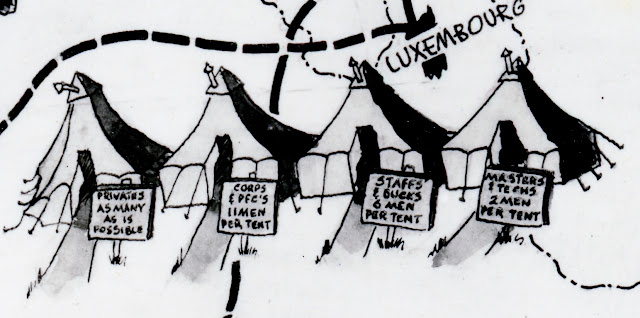

| Perspective on the tent situation by a member of the 160th[5] |

We

are still having rain & cloudy & cold weather so there isn’t much to do

[i.e., the planes could not fly]. We have no stove in our tent & it sure

gets damp & cold in there. I sure hope they get some stoves soon.[6]

All planes flew

manually, so rain and overcast skies grounded them, leaving the ground crews

with time on their hands. Excitement was on the horizon, however, with the

unexpected arrival of an enemy plane.

[1] “General de Gaulle and his entourage proudly stroll

down the Champs Élysées to Notre Dame Cathedral for a Te Deum ceremony

following the city's liberation on 25 August 1944,” photograph, Imperial War

Museum, Ministry of Information, Second World War Press Agency Print Collection

(http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205015974),

photograph HU 66477, public domain; as reproduced in Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19139629

: accessed 29 June 2018).

[2] “The Push through France,” map created with Google Maps (https://www.google.com/maps : accessed

28 June 2018).

[3] Jack J. Kellar (Luxembourg) letter to “Dearest Alice”

[Alice (Streeter) Kellar] (Santa Rosa, California), 17 October 1944, excerpts.

[4] Jack J. Kellar, interview by Judy Kellar Fox,

December 1993; cassette tape recording and transcription held by the author.

[5] Ralph C. Fritz, illustrated map of the 160th

Squadron in the ETO, 15 August 1945, detail; “Life with the 160 Tactical

Reconnaissance Squadron,” collection of eleven photographs, U.S. Army Air

Force,